Peter Yankala is well-known for Phillips Men’s Wear, a store he has owned since 1974—a stunning 48 years of service to Barringtonians. Now helping to outfit the 4th-generation progeny of his earliest customers, Yankala also passionately pursues avocations including photography, architecture, and travel. A certified specialist on the work of Frank Lloyd Wright, Yankala introduces us to a little-known lakeside estate, a hideaway built by Wright and owned by former long-time residents of Barrington Hills. Bought in near tear-down condition, Susan and John Major have restored the Wright property to its former glory, honoring the original architectural design. It will be the subject of Yankala’s upcoming book, “Penwern/A Visual Study” (Spring 2023). Built from 1900 to 1903, the estate named Penwern is complete, ready to offer refuge and joy for another 100 years for its owners, and their family, friends, and guests. We asked Peter Yankala to share his experience and photography of Penwern and the story of how the Majors brought this gem back to life.

The Fred B. Jones House, named Penwern, had curious beginnings in 1900, with questions still not answered over a century later. There is not a lot of history on Jones, or why the estate started with the boathouse first. There is little known about the man who commissioned it, or the origins of the design inspiration. A man of means, he was known to be gregarious, with a reputation for nifty and frequent parties. He lived with and cared for his mother, keeping her under roof for a lifetime. What is more traceable, however, is the designer and architect. Frank Lloyd Wright was introduced to the opportunity to build the estate—one of only 40 in this scope of the nearly 1,100 residential projects primarily in the Midwest—by a next-door neighbor in Oak Park.

Wright’s career was exploding at the turn of the 20th century. He would enter decades of being a superstar of his day. He lived just north of a man in Oak Park who would become his friend, and in a way, business partner. His name was Henry Wallis. In 1895, Wallis was a star in his own right as a resourceful real estate salesman, investor, and developer. His investing instincts led him to Delavan Lake, in Delavan, Wisconsin, where he struck a deal to purchase a large stretch of land along the south shoreline of the lake.

Henry Wallis began to market his property starting with friends and neighbors near his residence in Oak Park and River Forest. Fred Bennett Jones was a Chicago industrialist on the supply side of the exploding rail industry across the country. He lived in Oak Park, Illinois, and was a friend and neighbor of Henry Wallis. Wallis was a visionary in some aspects of emerging Chicago lifestyle. It is not known if Wallis might have been considering opening a resort. That business model was on the minds of many real estate speculators of the time.

Chicagoans were anxious to exit the city during the unbearable Chicago summers. By the property records of the day, he divided most of the land into small lots to build and sell lake cottages. But in that plat of survey a large portion, about 50 acres, was left without lot lines. And his first sale came as an estate size swath, to a Chicago industrialist, who may have been jumping on an emerging social status of lake home ownership. There was an appetite to escape the city during a period in the Midwest which seemed to be plagued by summer heat waves, droughts, and subsequent fires.

Upon selling each parcel, Wallis invariably made a point to suggest using his friend, architect Frank Lloyd Wright, for the design of the summer home. It was advice the Ross, Spencer, and Johnson clients followed in coming years, doing just that. More immediately, Wallis took his own advice and developed a comparatively moderate estate and farm next to property he sold to Fred B. Jones—thrilled that Jones had accepted his recommendation of Wright—Wallis hired him as well, but he never moved in, electing to sell the finished cottage to his brother.

While four of Wright’s Delavan residential projects would have a spectacular Lake Delavan view, they would all fall short of the scope of what was to become Penwern. While the 1,900 sq. ft. boathouse was the first structure to be completed in 1900, the years of 1901 brought a 4,000-sq. ft. stable, the 6,800 main house, and in 1902, the 2,500 sq. ft. gate lodge. It was used for the estate caretakers and for an additional guest room. In total, this made the estate the largest of the land sales on Delavan Lake at just under seven acres.

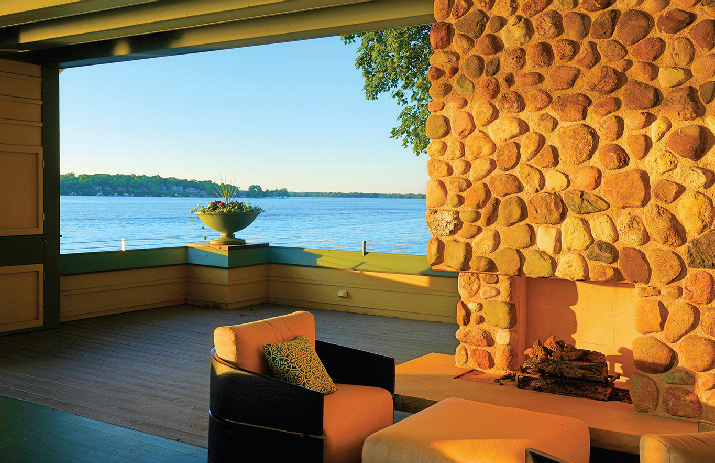

The Jones Estate, eventually named Penwern, started with a boathouse. A simple camping deck, and a lower, lake level space for shelter and living during the summer months, the boathouse was completed by the spring of 1900. Hunting, fishing, and sailing began to be great American pastimes. Fred Jones was a consummate socialite, and the grounds proved to be ideal for making camp and escaping from the heat, dirt, and noise of the big city, with friends invited for weekends from all over the Midwest. The style was pavilion-like with an open-air format, and a massive fireplace set off center on the deck. It had a spectacular east-to-west view of the lake, while looking to the opposite north shoreline.

The boathouse was appointed with an upsweep at the roof ridgeline which seemed to be an influence Wright employed from his interest in Japanese culture and architecture, although it would be five years before his first visit to Japan in February 1905. The full framework of the boathouse may be derived from the style of a Japanese torii gate—the simple structure of right and left uprights, and a cross member exceeding the side posts. Torii gates throughout Japanese culture were often placed within a Shinto shrine, used symbolically to mark the transition from the mundane to the sacred. You can easily see this intent as you enter the shoreline side of the structure.

Wright used local glacial stone in many aspects of the boathouse starting with a retaining wall set back and buried around three sides of the structure. His intent was to keep the hydraulic pressure from pushing on the foundation and footing of the structure. The recognition of future problems often present when building into a hillside must have been apparent.

Wright engineered a stone buttress to hold the wall plumb. Now, 115 years after construction, the footings and foundation walls remain, however the original boathouse structure does not. It had been lost in a 1978 fire and was replaced with something akin to only decking. And there it sat unwilling to give up its footprint, but unable to find the resource to rebuild. It would sit until new stewards and owners appeared.

In the winter of 1992, Susan and John Major, both Chicagoland executives, started looking for a summer cottage near their suburban home in Barrington Hills, Illinois. They were and remain members of the Barrington Hills Country Club. Barrington was home for raising their two young children at the time. Friends, some of whom were already Lake Delavan summer residents, suggested looking along the Lake Delavan shoreline.

There was a sizeable home on the shore in ramshackle— “a shambles”—condition for sale. The house had lake frontage, but only the foundation where the boathouse once stood. And, while the Majors were aware that Frank Lloyd Wright had his hand in what remained of the estate, their vision was unclear in seeing more than a place that needed a lot of work, yet, might just be the perfect lake house for them. The Gate Lodge and stables were split off from the original land footprint and were no longer part of the once extensive estate. As the property’s fourth owners, they purchased the estate in 1994 and while they had their doubts, the home and land called to them. “We were only slightly ahead of the wrecker’s ball,” John Major said.

John Major admits there was not a spark for the structure remaining, but there was a calling from the setting, and a keen awareness that “you cannot change the land”. As the new summer homeowners swept, cleaned, and spent the first few weeks in the house, they discovered failings and deterioration which led them to consider demolishing the house and starting from scratch sometime, but not just yet. Summer activities were beginning and while leaking roofs and missing glass windows became a priority on the to-do list, the Major family enjoyed their home and the adventures presented each summer weekend.

After the first summer and quick fixes to make the summer house livable, the Majors decided to celebrate their first year with friends up and down the lakeshore by arranging a New Year’s gathering. Party plans were completed, and guests were invited. The very afternoon of the event the Majors ran into a problem—there was no water. The Wisconsin frost had settled deep enough to freeze the 100-year-old water pipes on the grounds which supplied the house.

Crestfallen about the event, John managed to introduce a secondary pipeline hours before the first guest arrived, tapping into the still-functioning horse stable water line and rescued the evening. The incident was pivotal, however, in the future restoration of the entire estate. Closing the house down for the rest of the winter, a plumbing company was brought in to dig water lines deeper and below the frost line to correct the problems in anticipation of the next year’s winter.

One among the 17 million fairgoers at the World’s Columbian Exhibition of 1893 was a struggling 26-year-old Chicago architect named Frank Lloyd Wright. The exposition would prove to be a watershed in Wright’s relationship with Japanese aesthetics. Although he had collected and traded prints from Japan for years, the fair was his first direct contact with Japanese buildings. Within the decade, Wright would design his first houses drawing on the deep roof overhangs and the stress on horizontal lines witnessed at the Japanese pavilion.

During the first year, Susan and John Major reflected upon the house and while there seemed to be Wright’s signature in and over much of the house, there was plenty that never made sense. “We knew who Wright was but were not particularly on board with the structure for a summer home,” Susan said. It was by all accounts clumsy and dark, with non-Wright-designed room additions, about 2,700 sq. ft. of them, the home grew from the original 6,800 sq. ft. to near 10,000 sq. ft.—with much of the space having inadequate natural light and ventilation. There were walls added inside and rooms erected on what were meant as part of Wright’s classic open areas on the three grand curvilinear porches.

The concerns about the house, along with the conflict of whether to demolish or remodel, came to end on a spring day when the plumbing contractors were finishing up the underground water lines. It coincided with a visit by John to inspect the work. Satisfied with the work and noticing heavy equipment was still on site, he asked the backhoe operator to place his bucket at the roof line intersection of what John believed to be an addition to the original house on the west side, then said “pull it down”.

That first measure revealed the original wall of the house and a gallery of leaded glass windows that were sealed in the wall and hidden from both sides. That first demolishing swipe to expose a portion of the original home set in motion the Major’s commitment to not replace or remodel the house, but rather, restore it. But first, he would need to assuage the local newspapers, preservationists, and concerned neighbors who accused the Majors of destroying a FLW original, in that John and Susan went about removing enclosures and walls and space not original to the plans, using photos available to them.

The demo was easy, but what was Wright’s original scheme? That question was answered when a resident across the lake, upon reading of the demolition, decided to see for himself what was being done to the house. He brought with him, though not sure he was going to tender them, 17 of the 64 original drawings done by Wright of Penwern and its four main structures. Those drawings were inadvertently found in his home’s drawers, and the neighbor was not sure from whom or how they got there.

Susan and John Major had expanded their home in Barrington Hills offering experience in renovation which lent confidence for the full restoration of their summer home on Delavan Lake. “I think we both had energy, we were young,” Susan said. “So, we had it, what we thought was a knack for it, and the interest. But we didn’t know about Frank Lloyd Wright, so that was a real learning process for us.”

What was the catalyst for the Majors to their long-term commitment to restoring the property to Wright’s original architectural designs, albeit employing more secure, modern structural materials?

“For me, it was when we found the drawings. That was one of them, because there was a blueprint to turn this into something priceless,” John said. “If I hadn’t found the 17 drawings, I’m not sure I would have been as motivated.”

“You’re right,” Susan said. “Because that became the goal, it was always to get back to the original footprint. I just know for me it was when we got the art glass windows started. We were afraid they would fall out.”

Penwern was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974. Will it become a museum one day? The Majors, now California residents, say no—it will remain in the family for their two children and grandchildren to enjoy, and to continue the excellence of its stewardship. It is available through educational programs with several university programs as a teaching tool.

Susan and John Major have painstakingly restored Penwern to Frank Lloyd Wright’s original design, keeping everything, including the color palettes, original except in some areas, stronger and longer-lasting building materials. When the gatehouse had to be torn apart to replace the flooring, every glacial rock from its foundation and walls was returned and put back into place in the building. The additions were torn off which opened light into the living spaces and restored the architectural integrity. And the boathouse, where it all started, was rebuilt to its original glory, complete with its torii gate style roofline that reflects a place on the water that offers transition from the mundane to a place to be enjoyed and revered.

Frank Lloyd Wright was close to his mother, whose parents emigrated to the United States from a cottage named “Pen-y-wern” near Llandysul, Wales. The name “Penwern” is Welsh for “at the head of the field,” and may have suggested how his grandparent’s cottage was situated on the farmland in Wales. Having only known his grandmother as a toddler, Wright heard stories of the courage and fortitude it took for his maternal grandparents to leave everything behind, bringing several children along for a new, better life. If his grandparent’s journey across the ocean in the mid-1800s had not happened, would Frank have had the formative influences that shaped him into “the greatest American architect of all time”? 1

Possibly not. But they did make the treacherous journey, and the Penwern estate serves as a fitting name for a man who was, and will forever remain, at the head of his field.

[1 stated in 1991 by the American Institute of Architects]

Share this Story